Japan’s newly installed environment minister, Shinjiro Koizumi, wants the country to close down nuclear reactors to avoid a repeat of the Fukushima catastrophe in 2011.

The comments by the son of former prime minister Junichiro Koizumi, himself an anti-nuclear advocate, are likely to prove controversial in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which supports a return to nuclear power under new safety rules imposed after Fukushima.

“I would like to study how we will scrap them, not how to retain them.”

—Shinjiro Koizumi, Japanese environmental minister

“I would like to study how we will scrap them, not how to retain them,” Shinjiro Koizumi said at his first news conference late on Wednesday after he was appointed by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Japan’s nuclear regulator is overseen by Koizumi’s ministry.

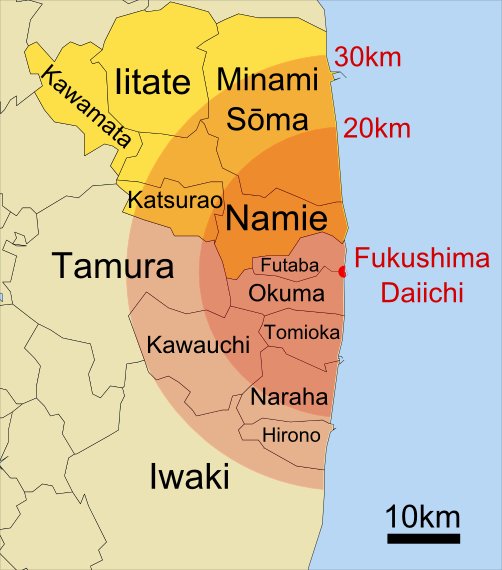

Three reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi station run by Tokyo Electric Power melted down after being hit by a massive earthquake and tsunami in March 2011, spewing radiation that forced 160,000 people to flee, many never to return.

Let’s have a look on what happened in 2011.

The Great East Japan Earthquake of magnitude 9.0 at 2.46 pm on Friday 11 March 2011 did considerable damage in the region, and the large tsunami it created caused very much more.

The earthquake was centred 130 km offshore the city of Sendai in Miyagi prefecture on the eastern cost of Honshu Island (the main part of Japan), and was a rare and complex double quake giving a severe duration of about 3 minutes.

An area of the seafloor extending 650 km north-south moved typically 10-20 metres horizontally. Japan moved a few metres east and the local coastline subsided half a metre. The tsunami inundated about 560 sq km and resulted in a human death toll of about 19,000 and much damage to coastal ports and towns, with over a million buildings destroyed or partly collapsed.

Eleven reactors at four nuclear power plants in the region were operating at the time and all shut down automatically when the quake hit. Subsequent inspection showed no significant damage to any from the earthquake.

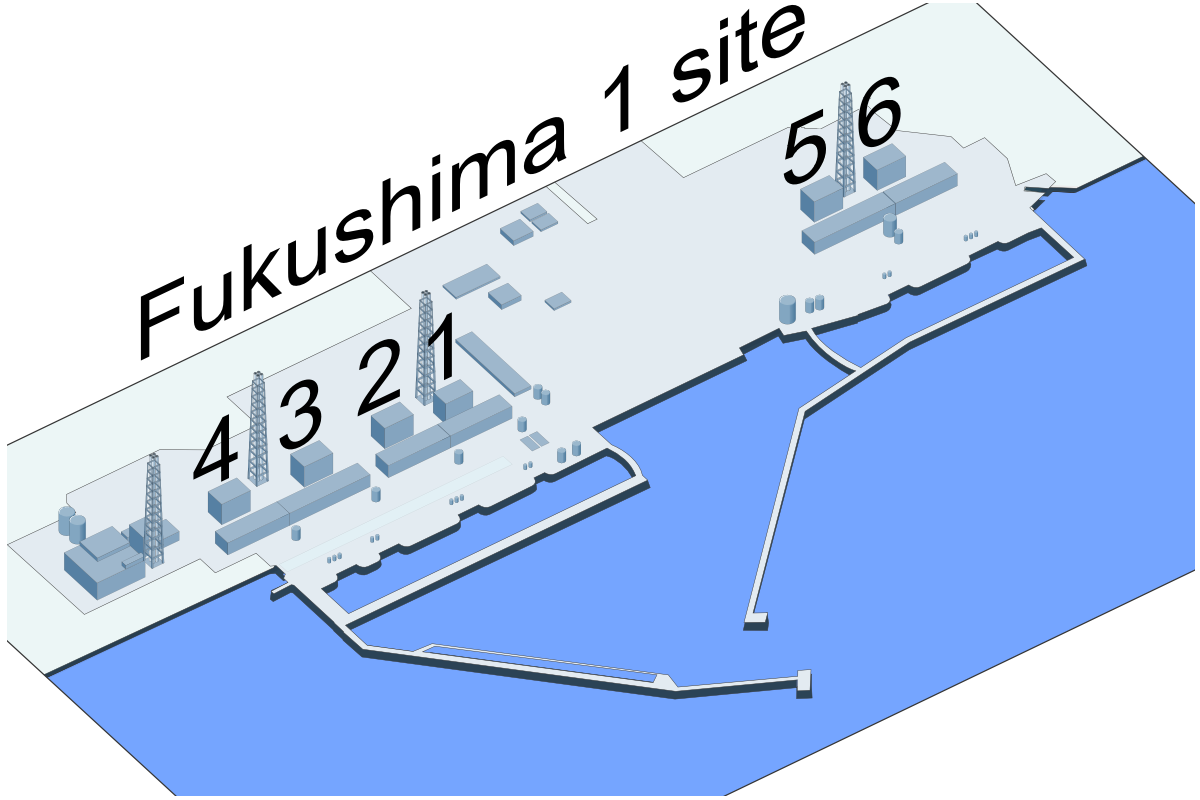

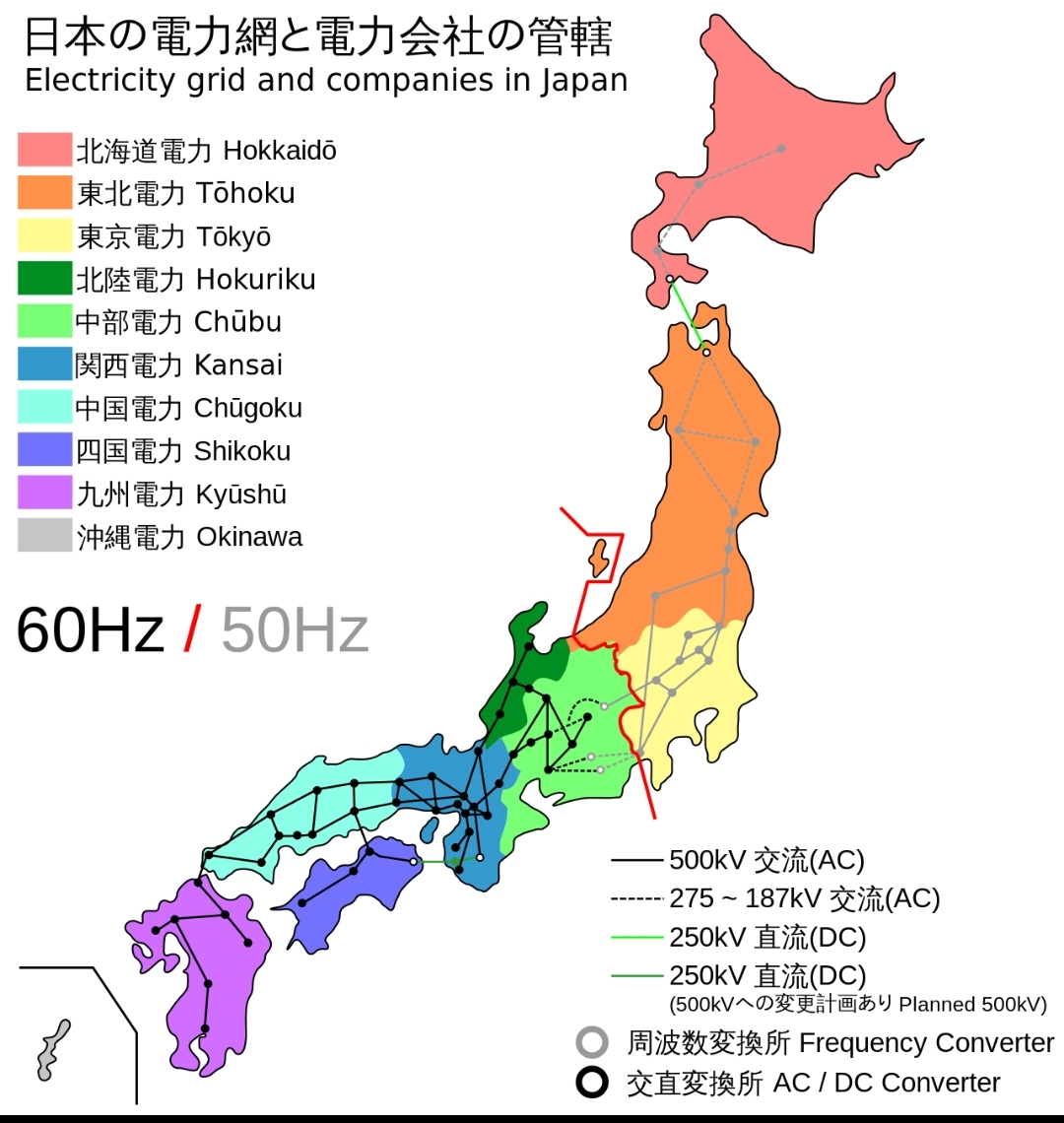

The operating units which shut down were Tokyo Electric Power Company’s (Tepco) Fukushima Daiichi 1, 2, 3, and Fukushima Daini 1, 2, 3, 4, Tohoku’s Onagawa 1, 2, 3, and Japco’s Tokai, total 9377 MWe net. Fukushima Daiichi units 4, 5&6 were not operating at the time, but were affected. The main problem initially centred on Fukushima Daiichi units 1-3. Unit 4 became a problem on day five.

The reactors proved robust seismically, but vulnerable to the tsunami. Power, from grid or backup generators, was available to run the residual heat removal (RHR) system cooling pumps at eight of the eleven units, and despite some problems they achieved ‘cold shutdown’ within about four days. The other three, at Fukushima Daiichi, lost power at 3.42 pm, almost an hour after the quake, when the entire site was flooded by the 15-metre tsunami.

This disabled 12 of 13 back-up generators on site and also the heat exchangers for dumping reactor waste heat and decay heat to the sea. The three units lost the ability to maintain proper reactor cooling and water circulation functions. Electrical switchgear was also disabled. Thereafter, many weeks of focused work centred on restoring heat removal from the reactors and coping with overheated spent fuel ponds. This was undertaken by hundreds of Tepco employees as well as some contractors, supported by firefighting and military personnel.

Some of the Tepco staff had lost homes, and even families, in the tsunami, and were initially living in temporary accommodation under great difficulties and privation, with some personal risk.

A hardened emergency response centre on site was unable to be used in grappling with the situation, due to radioactive contamination.

Three Tepco employees at the Daiichi and Daini plants were killed directly by the earthquake and tsunami, but there have been no fatalities from the nuclear accident.

Among hundreds of aftershocks, an earthquake with magnitude 7.1, closer to Fukushima than the 11 March one, was experienced on 7 April, but without further damage to the plant. On 11 April a magnitude 7.1 earthquake and on 12 April a magnitude 6.3 earthquake, both with epicenter at Fukushima-Hamadori, caused no further problems.

In June 2016 Tilman Ruff, co-president of the political advocacy group, the “International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War” argues that 174,000 people have been unable to return to their homes and ecological diversity has decreased and malformations have been found in trees, birds, and mammals. Although physiological abnormalities have been reported within the vicinity of the accident zone, the scientific community has largely rejected any such findings of genetic or mutagenic damage caused by radiation, instead showing it can be attributed either to experimental error or other toxic effects.

Five years after the event, the Department of Agriculture from the University of Tokyo (which holds many experimental agricultural research fields around the affected area) has noted that “the fallout was found at the surface of anything exposed to air at the time of the accident. The main radioactive nuclides are now caesium-137 and caesium-134”, but these radioactive compounds have not dispersed much from the point where they landed at the time of the explosion, “which was very difficult to estimate from our understanding of the chemical behavior of cesium”.

In February 2018, Japan renewed the export of fish caught off Fukushima’s nearshore zone. According to prefecture officials, no seafood had been found with radiation levels exceeding Japan safety standards since April 2015. In 2018, Thailand was the first country to receive a shipment of fresh fish from Japan’s Fukushima prefecture. A group campaigning to help prevent global warming has demanded the Food and Drug Administration disclose the name of the importer of fish from Fukushima and of the Japanese restaurants in Bangkok serving it. Srisuwan Janya, chairman of the Stop Global Warming Association, said the FDA must protect the rights of consumers by ordering restaurants serving Fukushima fish to make that information available to their customers, so they could decide whether to eat it or not.

In July 2018, a robotic probe has found that radiation levels remain too high for humans to work inside one of the reactor buildings

Most of Japan’s nuclear reactors, which before Fukushima supplied about 30% of the country’s electricity, are going through a re-licensing process under new safety standards imposed after the disaster highlighted regulatory and operational failings.

Japan has six reactors operating at present, a fraction of the 54 units before Fukushima. About 40% of the pre-Fukushima fleet is being decommissioned.

Shinjiro Koizumi’s father, a popular prime minister now retired from parliament, became a harsh critic of atomic energy after the Fukushima nuclear crisis.