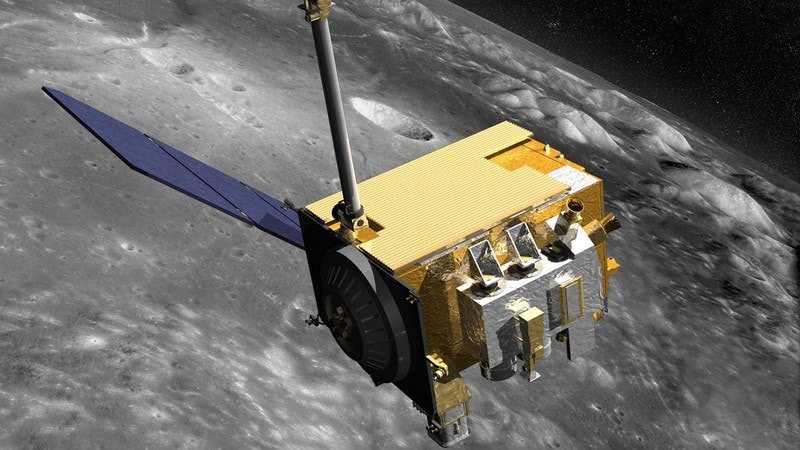

Scientists, using an instrument aboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), have observed water molecules moving around the dayside of the Moon.

A paper published in Geophysical Research Letters describes how Lyman Alpha Mapping Project (LAMP) measurements of the sparse layer of molecules temporarily stuck to the surface helped characterize lunar hydration changes over the course of a day.

NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) spacecraft has observed water molecules moving around the dayside of the Moon, a finding that may prove beneficial as the agency plans to put astronauts back on the lunar surface.

Lyman Alpha Mapping Project (LAMP) — the instrument aboard LRO — measured sparse layer of molecules temporarily stuck to the Moon’s surface, which helped characterise lunar hydration changes over the course of a day, revealed the paper published in Geophysical Research Letters.

“The study is an important step in advancing the water story on the Moon and is a result of years of accumulated data from the LRO mission,” said John Keller, LRO deputy project scientist from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Maryland.

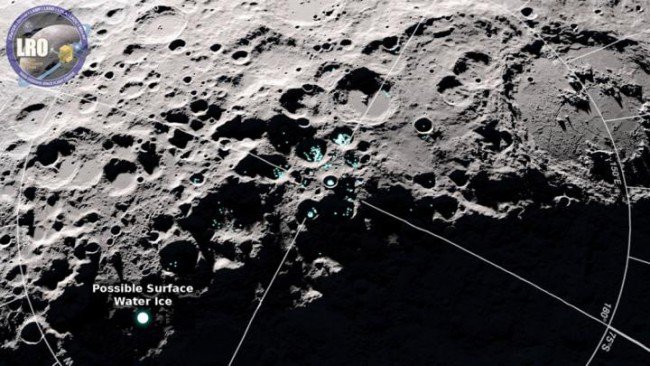

Until the last decade, scientists thought that the Moon was arid, with any water existing mainly as pockets of ice in permanently shaded craters near the poles.

More recently, they identified surface water in sparse populations of molecules bound to the lunar soil, or regolith.

But, the amount and locations were found to vary based on the time of day. The lunar water is more common at higher latitudes and tends to hop around as the surface heats up.

Scientists had hypothesised that hydrogen ions in the solar wind may be the source of most of the Moon’s surface water. As a result, when the Moon passes behind the Earth and is shielded from the solar wind, the “water spigot” should essentially turn off.

However, the water observed by LAMP does not decrease when the Moon is shielded by the Earth and the region influenced by its magnetic field, suggesting water builds up over time, rather than “raining” down directly from the solar wind.

“These results aid in understanding the lunar water cycle and will ultimately help us learn about accessibility of water that can be used by humans in future missions to the Moon,” said lead author Amanda Hendrix, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute.

“Lunar water can potentially be used by humans to make fuel or to use for radiation shielding or thermal management; if these materials do not need to be launched from Earth, that makes these future missions more affordable,” Hendrix added.