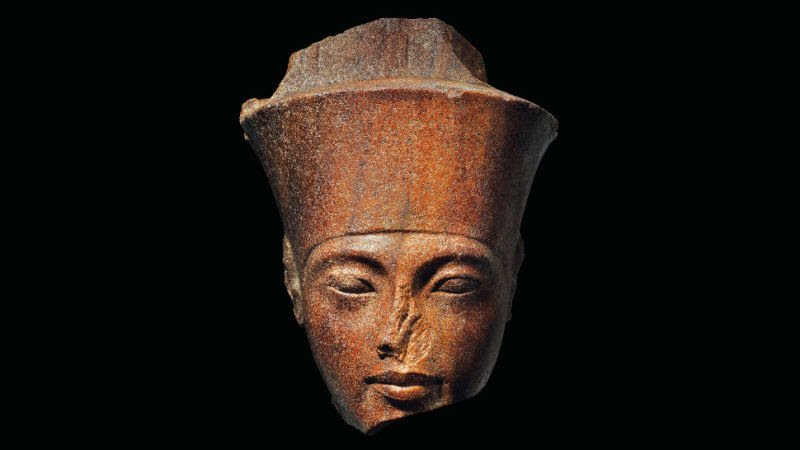

A 3,300-year-old sculpture of Tutankhamun’s head has been auctioned off at Christie’s for $6 Million, despite claims from the Egyptian government that the relic was stolen.

The 11-inch-tall bust, made from brown quartzite, has damage to the nose, ears, and chin, but is in otherwise excellent condition, according to Christie’s, a London-based auction house. The sculpture is a depiction of the ancient Egyptian god Amen, and fashioned to look like the pharaoh Tutankhamun. An unnamed collector purchased the stunning 3,300-year-old relic for £4,746,250 ($5,936,372) at an auction on July 4.

“This face is recognizable among a thousand Egyptian royal faces,” noted Laetitia Delaloye, London Head of Ancient Art & Antiquities, at the Christie’s website, pointing to the pharaoh’s almond-shaped eyes, high cheekbones, and prominent top lip. “We are honoured to present this head to auction for the first time in its history. It has been very well known on the market, and has been published and exhibited many times over the past 35 years,” she said.

Christie’s went ahead with the auction despite protests from Cairo and appeals to the British government by Egypt’s ambassador in London.

The north African country claims rightful ownership of the piece, saying it holds the rights under its laws, according to ABC News. Prior to the auction, the Egyptian foreign ministry demanded that Christie’s disclose documentation detailing the statue’s ownership.

“They never tell us about the origin, about how they bought it from Egypt, who has ownership of this piece,” said Zahi Hawass, the former Egyptian antiquities minister, as reported by CBS news. “They have no evidence of that but we do think that this is a part of our heritage.”

Indeed, the history of this relic is shrouded in mystery. Since the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in the 1920s, the bust has passed through several owners, finally landing in a private German collection in 1985. The relic has now moved on to yet another owner, despite claims from Egypt that the relic was stolen.

Christie’s disagreed, saying it carried out “extensive due diligence” to prove the ownership of the statue, and that it went “beyond what is required to assure legal title,” according to the Associated Press. A U.K. government official said “they expect all sales to go in accordance with the law and that this is a matter for Christie’s,” reported CBS.

This is not the first time Egypt has demanded the return of an artifact, nor is it likely to be the last. The Rosetta Stone kept at the British Museum, for example, is one such item. This latest incident is part of a growing trend, in which nations are demanding the return of ancient artifacts taken from their territory by foreign archaeologists and collectors.

Indeed, a strong case can be made that ancient relics, human remains, and other items of archaeological, historical, and cultural significance, if taken without consent, should be repatriated when a country asks for their return. Sadly, too many countries are finding it hard to shake their imperialistic habits.